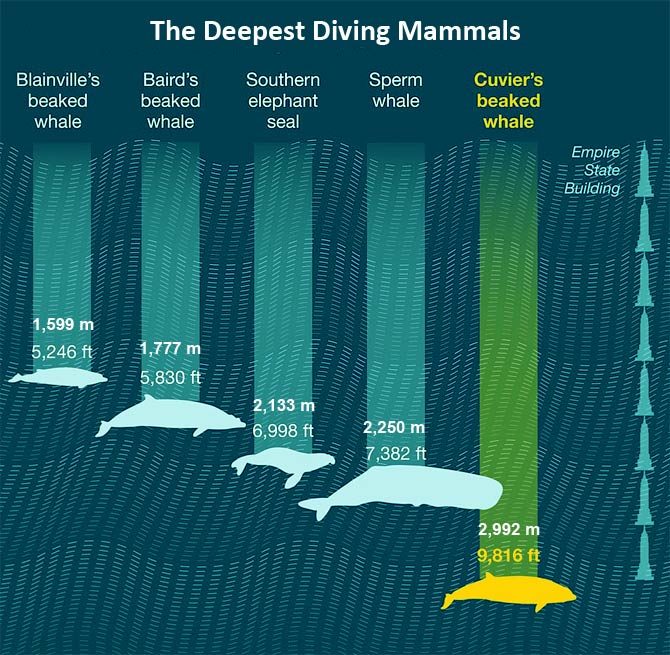

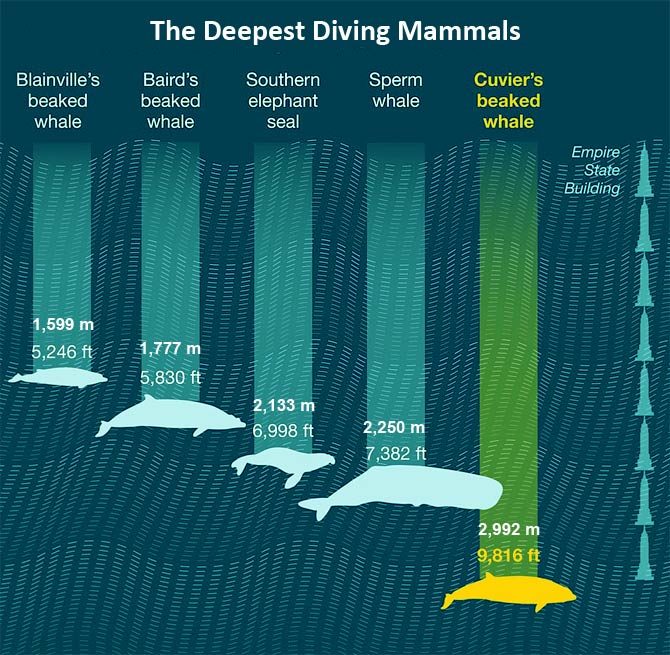

The deepest diving mammals

When we visit the ocean, we are presented with a vast horizon textured by the wind and waves. We can dapple in her margins, snorkeling or SCUBA diving within the reach of the sun’s light. But it is the Deep where our imagination mingles with things we’ve only heard about; swimming with all manner of beasts adapted to an alien environment, with forms not subject to gravity, but strangely adapted to the physical bounds of their environment.

Bio-luminescent creatures appear like starlight in the dark Abyss, sensing their surroundings through sound and turbulence, and putting on lightshows to attract or frighten – or remaining dark until just the right moment…

But one of the imponderable aspects of the Abyss we don’t consider is the pressure on these creatures at the depths they dive.

In our air-saturated habitat, we are subject to barometric variations of ‘one atmosphere,’ which is ~100,000 Pascals (14.6 lbs. sq. inch.) at sea level, and about 30% of that at the top of Mt. Everest (8,848m or 29,000’). This is enough to gum up human metabolisms a bit, but people have visited without oxygen and returned to tell the tale.

This changes significantly when diving into the ocean, where pressure increases by one atmosphere for every 10m (33ft.) in depth. If you are a diver, you know this by the annoying need to equalize the pressure in your ears every few meters. And you may also know this as a SCUBA diver about decompression routines as you rise to the surface.

So these deep-diving animals have some remarkable adaptations to mediate the extremes in pressure they regularly transverse.

The shallowest deep-diver on our chart, the Blainville’s Beaked whale, can mediate 160 atmospheres of pressure – equivalent to 2,320 lbs.in2, and the Cuvier’s Beaked whale can mediate 300 atmospheres or 4,223 lbs. in2. This later pressure is equivalent to having the weight of a Toyota Tundra distributed to every square inch of their body surface (which, as an aside, you can now get as a Hybrid 😉

Of course their bodies are somewhat equivalent in density to water, and as such are not really compressible. But what is compressible is the air the animals bring down there with them. So the 32-liter lung capacity of the Cuvier’s beaked whale is compressed down to ~ 1 liter in volume at depth.

One adaptation is that they distribute this air throughout the tissues and fluids of their bodies, making it available to the muscles and organs as they go about their business. When they head back to the surface, they do so in stages, following the sorts of decompression behaviors that are akin to decompression protocols human divers follow in surfacing from our deep, but much shallower dives.

How these once-terrestrial animals evolved to dwell in the deep is one of the marvels of our ocean. The other creatures that dwell in the abyss challenge our imagination. And it is a good thing that it’s dark down there, where visual beauty is not a evolutionary adaptive strategy…

Image credits: Paul J. Ponganis The deepest diving mammals, Comparative Physiology

Angler fish – Jarred Benny – Flicker.com