Researchers conduct a necropsy on a humpback whale that stranded in Brigantine, New Jersey. Photo courtesy of Marine Mammal Stranding Center

Researchers conduct a necropsy on a humpback whale that stranded in Brigantine, New Jersey. Photo courtesy of Marine Mammal Stranding Center

Is offshore wind killing whales? The short answer is “no,” qualified by “not really…”

This has been coming up a lot lately as the inevitable offshore wind projects grind into reality. Any change that is as dynamic as pivoting our growing energy thirst from fossil fuel to “sustainable” energy sources is bound to create indigestion throughout all socio-economic and industrial sectors.

In reaction to this, we are seeing a bit of a bar-fight between those who are all bought into offshore wind farms (OSW), and those who are not – with not a lot of room for those of us in between who may have a more nuanced perspective on our global energy future.

The latest gambit comes in the from those who claim that OSW is killing whales, and those who insist that “there is zero evidence” that OSW operations are having any impact on whales.

This is particularly the case along the Atlantic Seaboard, where there has been somewhat of a feeding frenzy to get steel in the water – and where there are a lot of complicated moving parts. Among these moving parts is the extremely endangered North Atlantic Right Whale (NARW). The population of the NARW has fallen over 35% in the last few years, and nobody seems to know the exact reason.

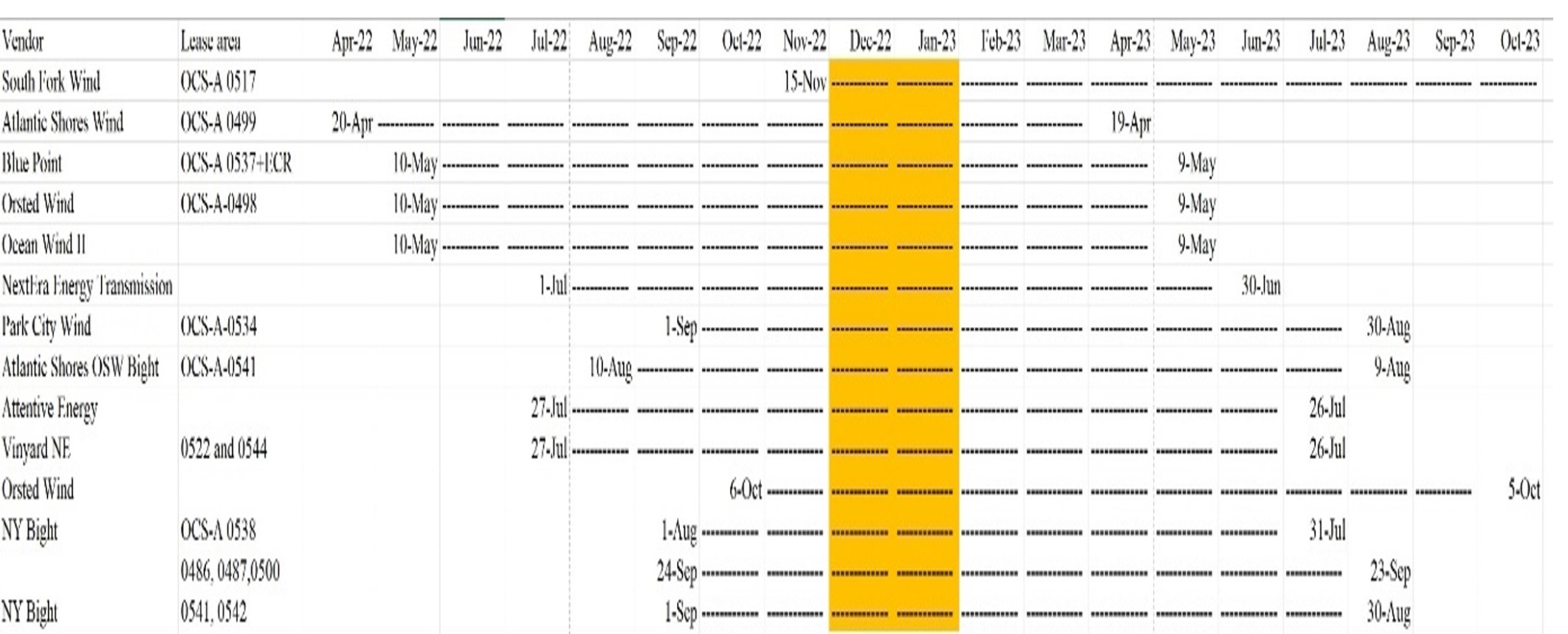

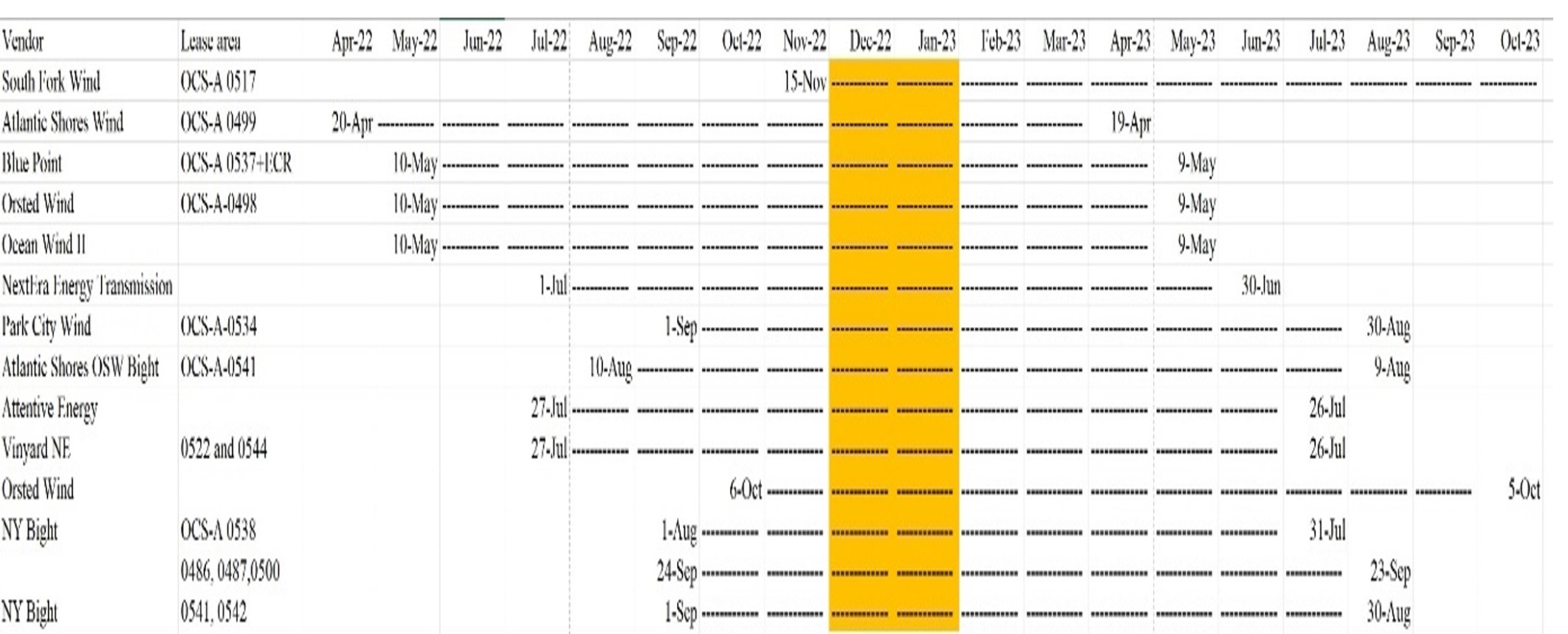

This came up last year when there was an unusual mortality event (UME) that occurred over December 2022 and January 2023.

Fortunately this UME did not include any NARW; they were mostly humpback whales, and one minke. But there were a lot of them in a two month period, which happened to coincide with a whole raft of site surveys occurring in the area.

The problem as I saw it was that NOAA fisheries issued 14 individual “Incidental Take Authorizations” (ITAs), which, while they may have accurately expressed the potential impacts of each of the individual surveys, they did not take into account the cumulative or collective impacts of all of the surveys when they were running concurrently and in close proximity. For this they should have issued an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), which could have given a “heads up” to the surveyors, allowing them to coordinate their efforts, and perhaps save a few whales.

Schedule of concurrent benthic surveys off NJ Dec. 2022 – Jan. 2023

But they didn’t, and so it so happened that all 14 surveys were running concurrently with the strandings (see chart above).

The metaphorical example I used was that if one of my neighbors was making all sorts of gawd-awful noises, I could leave the neighborhood and get some peace. But if I tried to leave the neighborhood, and found that everyone in the city was making gawd-awful noises, it might freak me out a bit.

So even if the noise exposure levels were “below regulatory thresholds,” the cumulative effect might have easily included elevated stress, fear, anxiety, and compromised vigilance.

I did not get any of the necropsy data from the strandings; whether they were associated with ship-strikes or entanglements, or they just threw themselves up on the beaches. But the impacts of 14 concurrent surveys can’t be ruled out as a variable in this tragedy.