Fish Ears 1 – What do fishes really hear?

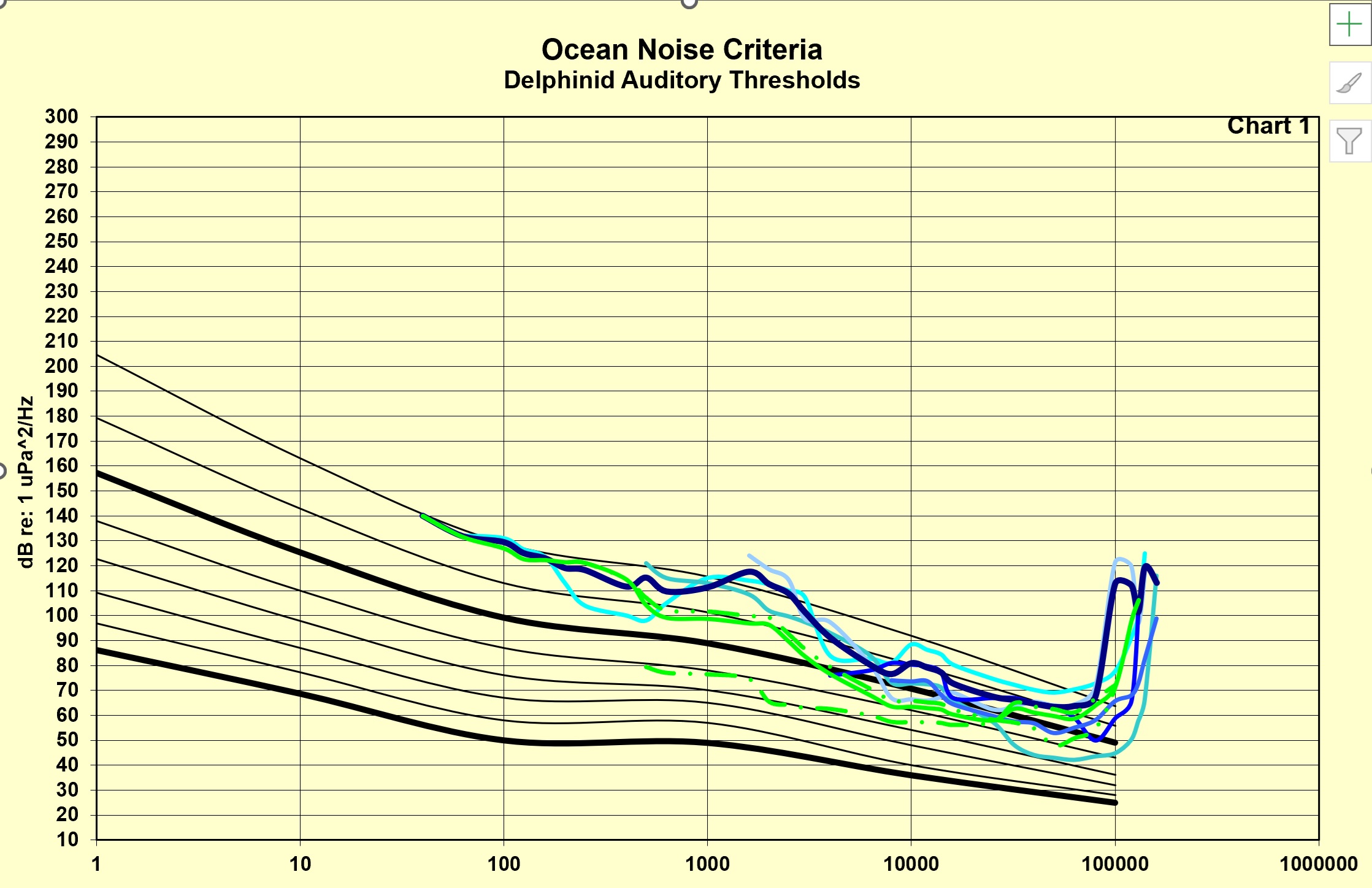

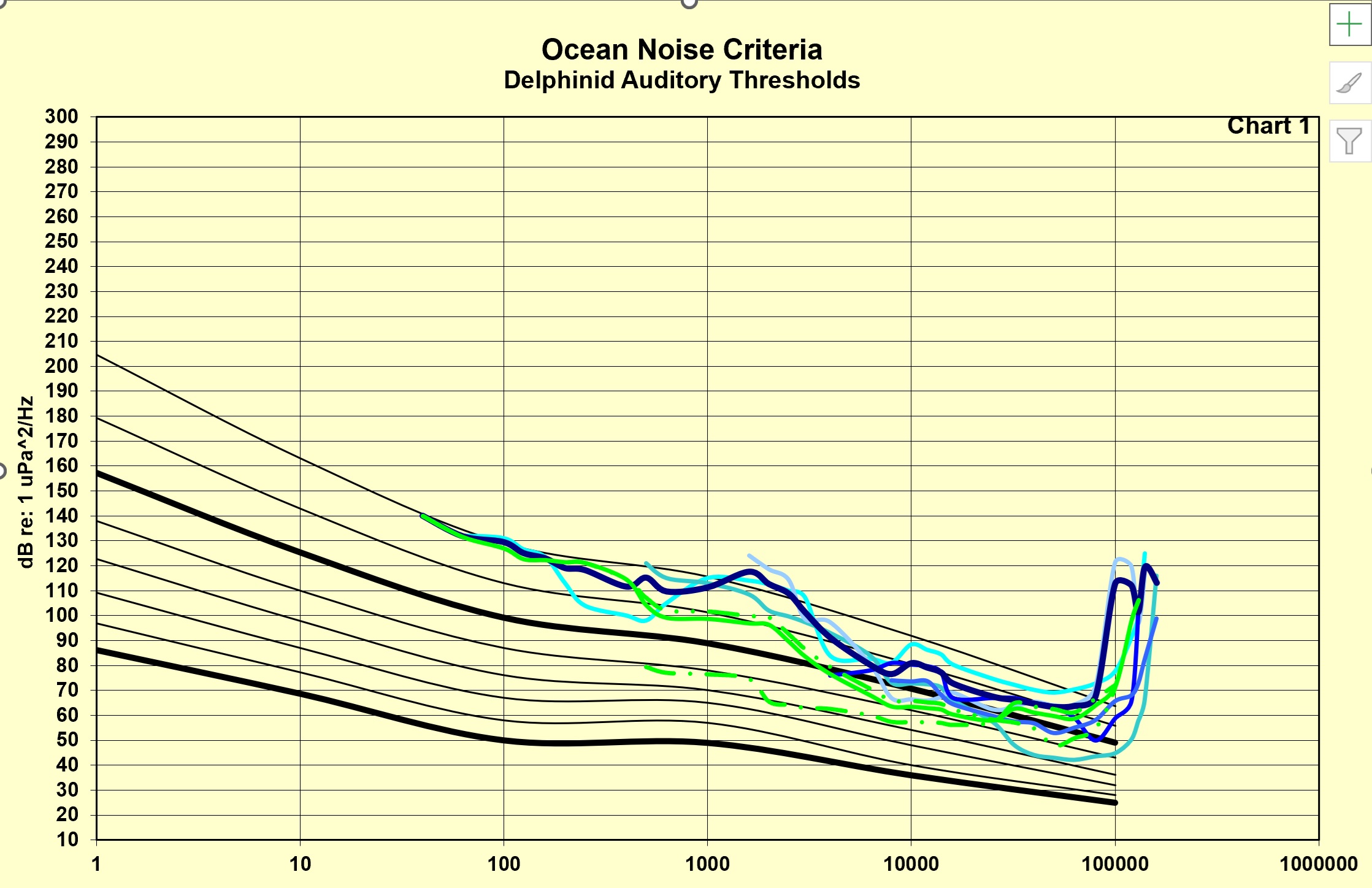

Delphinid hearing thresholds. The dark black lines bracket the “Wenz curves,”

Delphinid hearing thresholds. The dark black lines bracket the “Wenz curves,”

A preponderance of OCR’s ocean noise work has been driven by marine mammals – cetaceans, pinnipeds, and otters, because they are protected; but also because they navigate with sound much as we humans do. While terrestrial animal’s outer ears, ear drums, and middle ears are adapted to in-air hearing, the way acoustical energy is converted to neural signals through the cochlea is pretty similar in all mammals.

The cochlea is a mind-bogglingly complex spiraled bone chamber filled with complementary, ionically polarized lymphatic fluids, delicate cilia structures planted along thin membranes, and bundles of nerves that all ostensively convert physical motion of sound external to the body into electrical nerve impulses processed by the brain.

I explore the structural complexity of the cochlea in more detail in my book “Hear Where We Are: Sound, Ecology, and Sense of Place.” When I was working on this chapter I conferred with a physician pal, who immediately referred to the whole hearing mechanism as a “Rube Goldberg affair.”

We have other affinities with marine mammals – aside from the hair* and the lactation thing; we seem to all use sound in similar ways – locating ourselves in our surroundings, and using sound to communicate with conspecifics.

But what about the fishes? The phylogeny of fishes branch through so many distinct and different habitats and adaptations, their only common characteristic is that they all have a way to metabolize oxygen while underwater.

We all need to breath, but as water is such an effective conductor of sound, do fishes have other common acoustical adaptations that we are missing because we are not fishes?

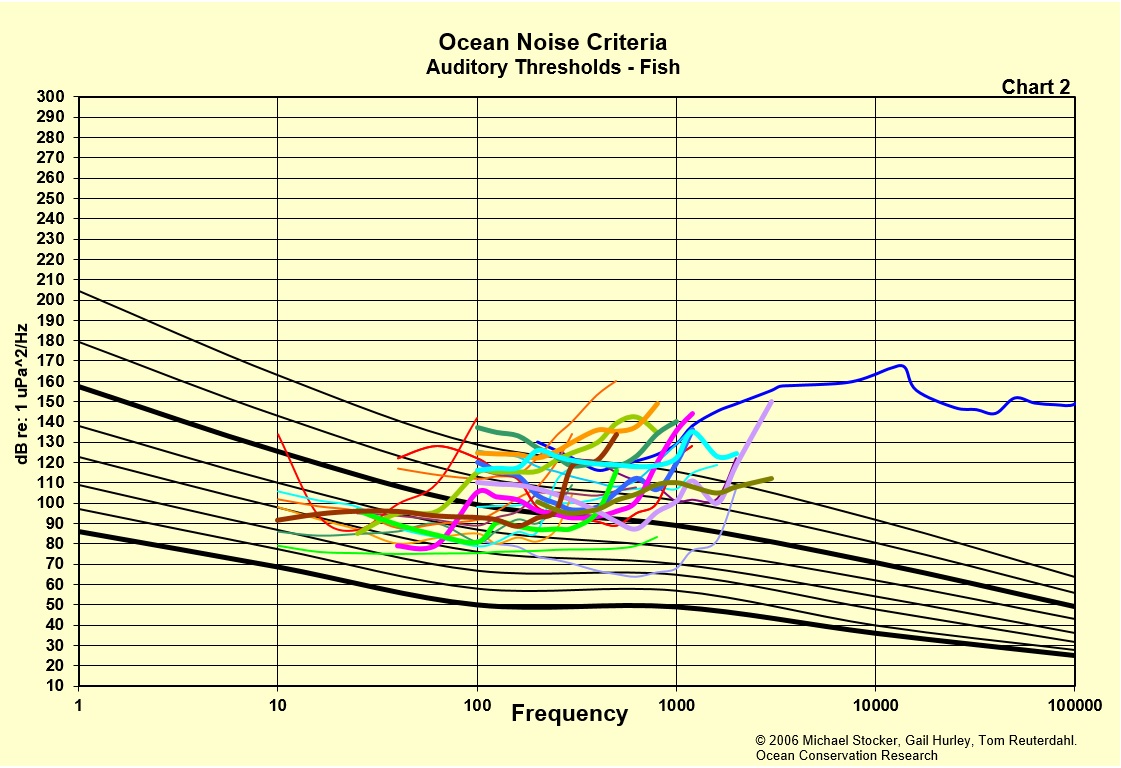

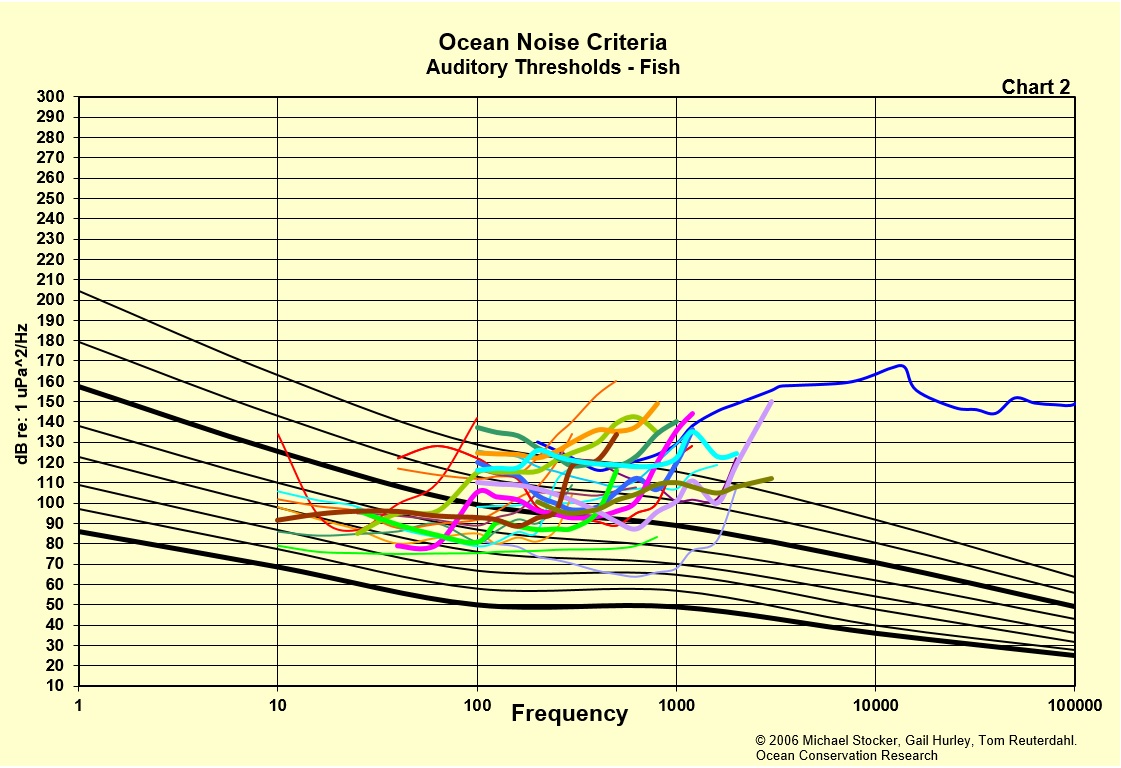

The hypothesis was that hearing thresholds of the animals would conform to the natural noise curves, because sensitivity to sound below the noise curves would just be buried in noise. The results for the marine mammals did confirm our hypothesis. But thresholds for the fishes did not; the average auditory sensitivity decreased by ~6dB to ~8dB per octave as the frequency increased.

There are a number of variables that need to be taken into account; the first would be how the fish thresholds were measured. The exposure testing sound levels were calibrated, but they were only measured with pressure sensitive hydrophones. It is now understood that while many fishes do have pressure-sensitive organs such as swim bladders that hook up to hearing systems, (translating pressure oscillations into neural impulses), we also now more fully understand that most fishes also have “particle motion” sensors – from cilia along their lateral lines, to ossicles in their inner ears that sense acceleration and physical displacement of their bodies moved by the acoustical energy born through water.

There are a number of variables that need to be taken into account; the first would be how the fish thresholds were measured. The exposure testing sound levels were calibrated, but they were only measured with pressure sensitive hydrophones. It is now understood that while many fishes do have pressure-sensitive organs such as swim bladders that hook up to hearing systems, (translating pressure oscillations into neural impulses), we also now more fully understand that most fishes also have “particle motion” sensors – from cilia along their lateral lines, to ossicles in their inner ears that sense acceleration and physical displacement of their bodies moved by the acoustical energy born through water.

And these are just dealing with the biophysics of sound of perception. Our next newsletter will explore the phenomenology of how fishes use sound in their respective habitats – and how that also might reflect in their sound sensitivities.

*Cetaceans are not typically associated with hairy bodies. Some are born with hair that quickly gets subsumed by blubber. Most mysticetes have sensory cilia on their rostrum, and sometimes other body areas, but these are not mammalian “hair,” they are sense organs akin to the cilia along the lateral lines of fishes (and the stereocilia found in our inner ears that translate cochlear particle motion into nerve impulses. Mysticete hair can be embedded in their outer blubber layer and not seen until the blubber falls away, such as the hair being revealed in the tail of this ‘ship-strike’ gray whale carcass as the blubber melts away in the sun.

Delphinid hearing thresholds. The dark black lines bracket the “Wenz curves,”

Delphinid hearing thresholds. The dark black lines bracket the “Wenz curves,” There are a number of variables that need to be taken into account; the first would be how the fish thresholds were measured. The exposure testing sound levels were calibrated, but they were only measured with pressure sensitive hydrophones. It is now understood that while many fishes do have pressure-sensitive organs such as swim bladders that hook up to hearing systems, (translating pressure oscillations into neural impulses), we also now more fully understand that most fishes also have “particle motion” sensors – from cilia along their lateral lines, to ossicles in their inner ears that sense acceleration and physical displacement of their bodies moved by the acoustical energy born through water.

There are a number of variables that need to be taken into account; the first would be how the fish thresholds were measured. The exposure testing sound levels were calibrated, but they were only measured with pressure sensitive hydrophones. It is now understood that while many fishes do have pressure-sensitive organs such as swim bladders that hook up to hearing systems, (translating pressure oscillations into neural impulses), we also now more fully understand that most fishes also have “particle motion” sensors – from cilia along their lateral lines, to ossicles in their inner ears that sense acceleration and physical displacement of their bodies moved by the acoustical energy born through water.